Metacognition in decision-making.

Abstract

The paper starts with a brief definition of metacognition and explains its parallel association with cognition based on the available research. The paper further elaborates the effects of metacognition on cognitive and attentional resources. The paper then discusses metacognition in decision making; limitations in human capabilities towards decision making; and various decision-making hypothesis and research related to framing, biases, and emotions. Emphasizing the different styles and approaches to decision making in expert and novice users, the paper analyzes and reviews the design of L&T Mutual Fund’s website. Along with analysis, relevant recommendations are provided thereby enabling users to make an informed decision.

1. Metacognition

(Meichenbaum, 1985) Metacognition refers to an individual’s knowledge about his or her cognitions i.e. being aware of the mental process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses. He further explained that metacognition is the individual’s ability to understand, control, and manipulate these cognitions. Examples of metacognitive activities include planning how to undertake a learning assignment, applying proper skills and strategies to problem-solving, assessing the progress with respect to task completion, observing and tracking the progress of one’s own understanding of literature, self-evaluating followed by self-rectifying, and becoming mindful of distractions.

(Flavell, 1979) Flavell developed a model for monitoring cognition based on metacognitive knowledge, metacognitive experiences, goals, and strategies. Metacognitive knowledge refers to that part of prior knowledge which lets an individual understand people, including themselves, as cognitive processors. Metacognitive knowledge comprises three variables: person; task; and strategy, that affects cognitive performance. The variable ‘person’ refers to an individual’s knowledge of their strengths and weaknesses while processing information. Task variable refers to the knowledge of a task in regards to its nature and processing requirements for its completion. The last variable ‘strategy’ refers to a person’s strategy or action plan that he or she can apply in order to complete the task successfully.

Metacognitive experiences refer to the feelings, approximations, or conclusions related to an ongoing or a completed cognitive process. For example, a feeling of not understanding a particular system or a feeling that a problem is well understood. The duration of these feelings or experiences can either be long lasting or short lived. Also, the content of these experiences can either be simple or complex. Metacognitive experiences correspond to effective learning (Flavell, 1979).

There are various types of metacognitive theories – tactic, informal, and formal. These are theories that focus on cognition (Schraw, & Moshman, 1995). Kuhn mentioned (as cited in Schraw, & Moshman, 1995) that these theories help one combine various facets of metacognition within a single framework. Kuhn proposes that metacognition surfaces very early in life in a very rudimentary form, like suggesting what is to come; and gradually evolves and strengthens to become more effective (Kuhn, 2000). Schraw and Moshman further stated that origination of metacognition is based on three primary factors – cultural learning, individual construction and peer interaction (Schraw, & Moshman, 1995).

Metacognition runs parallel to cognition and guides a person to apply different learning strategies and makes a decision about allocation of limited cognitive and attentional resources (Meichenbaum, 1985; Halpern, 1998). Thus, improving metacognitive efficiency can help reduce an individual’s cognitive load while he or she is performing a cognitive task. Hence, it imperative for designers to learn about various aspects of metacognition in order to enable easy learning, searching, and decision making.

2. Metacognition in decision making

Humans are not very good at making rational and logical decisions. This is because the available bandwidth for cognition and attention is limited and also because humans are constantly pounded by emotions (Slagter et al., 2007; Wickens et al., 2012, p. 249). The biology of human eye and mind is also to be blamed for this ineffectual determination of the optimal solution. As we learned in previous papers, the human eye and mind play tricks like an optical illusion – Müller-Lyer illusion, Ponzo illusion, Stroop effect, and priming effect. These tricks can lead to erroneous judgment. In Addition, it would be impossible to comprehend and weigh the huge amount of available information and narrow down on few or single optimal solution. This can lead to biases and misbeliefs that can interfere with rational decision making. Metacognitive abilities help beat these vulnerabilities and overcome biases in order to make rational and logical decisions. In the following sections, we will explore various factors that influence decision making

2.1. Biases in decision making

As mentioned earlier, biases can lead to erroneous judgments. (Croskerry, 2002) Croskerry catalogs and explains the different kinds of biases that can influence decision making. This section focuses on three kinds of biases – confirmation, anchoring, and omission.

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for evidence or recall information that confirms an individual’s hypothesis or beliefs, rather than search for information that disproves those hypotheses or beliefs. Confirmation bias is a very strong bias that can heavily influence decision making. Anchoring is another bias a designer must consider as it can, though occasionally, lead to quite devastating outcomes.

Anchoring bias is the tendency to heavily depend on specific information or features, usually the ones encountered first. It can lead to premature termination of thinking - failure to thoroughly consider significate information that wasn’t detected initially.

Omission bias is the tendency to incline towards inaction, as compared to actions since actions are more obvious. Fear too plays an important role in prioritizing inactions over actions, especially fear of being blamed for the actions resulting in bad outcomes (Croskerry, 2002).

2.2. Utility theory

(Edwards, 1954) proposed early utility maximization theory based on the assumption that humans naturally incline towards events and objects that have a positive outcome and ignore those that do not provide any benefit. Bigger the positive impact, more the value of that object. (Fishburn, 1970) further bifurcated the theory into straightforward and complex decision making. The straightforward decision making occurs in situations with a high degree of certainty. Conversely, complex decision making occurs in situations with a high degree of uncertainty including multiple outcomes surfacing at different levels of probability.

2.3. Prospect theory and framing effect

(Kahneman, & Tversky, 2013) critiqued the utility theory model for decision making governed by risk and proposed another model called prospect theory. According to prospect theory, decisions making is dependent on evaluation in terms of gains and losses. While the utility theory is based on the final outcome, prospect theory is based on deviation from current state or situation i.e. gain or loss.

Framing refers to the various ways of presenting a decision setting that can lead an individual to build a different representation of the presented setting (Kühberger, 1995). Kühberger further describes framing as “…general finding of risk aversion in the domain of gains, and risk seeking in the domain of loss…” Framing effects can thus, present the same outcome as either gain or loss, thereby influencing an individual’s decision. For example, students are more likely to enroll for a course having 93% of passing rate rather than a course having 7% failure rate. The prospect theory incorporates such framing effects.

2.4. Emotions and decision making

As mentioned in previous sections, in most of the hypothesis of decision making it is assumed that the decision is based on an evaluation involving cost-benefit analysis of the future outcome. However, emotions too play an important role in decision making. Bechara studied decision-making in neurological patients who could no longer process emotional information. The study suggested that apart from making decisions based on the future assessment of outcomes and the probability of those outcomes occurring, individuals also make decisions on an emotional level. He further concluded that occasionally emotions play a primary role in decision making (Bechara, 2004).

2.5. Experts in decision making

(Dew et al., 2009) Decision making approaches or styles varies significantly between experts and novices. Experts structure and approach problems in a way that is dramatically different from how novices deal with problems. Experts use effectual logic to make decisions whereas novices use predictive logic (Dew et al., 2009). Apart from domain knowledge, experts have an added advantage of being able to group incoming stimulus into units that are easier to identify and retrieve from the long-term memory and being held in the working memory (Lesgold, 1983). Thus, making cognitive resources available for parallel metacognitive activities such as considering alternative choices, applying proper skills and strategies to make optimum decisions, assessing their progress, or deciding to change strategies.

3. Design Review: L&T Mutual Funds website

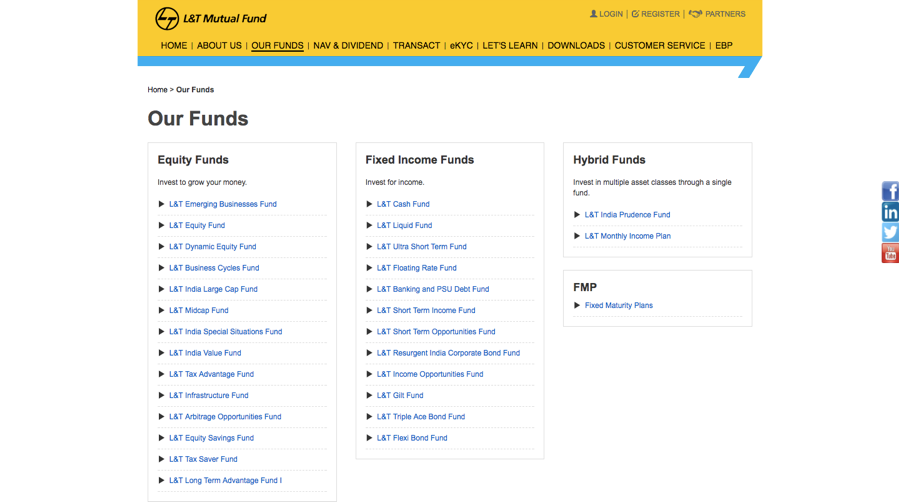

Figure 1: L&T Mutual Funds Website (http://lntmf.com/lntmf/lnt-our-funds) as on Nov 23, 2017

L&T mutual funds website, as shown in figure 1, offers 29 different types of mutual funds. Each fund is further divided into 2 sub-categories based on the payment plans – one-time payment or frequent monthly payments. These sub-categories further bifurcate into growth and dividend options. Thus, increasing the total number of choices to 116. This huge array of choices is likely to cause cognitive overload, diminishing the users’ ability to make a good or any decision at all. In addition, lack of filtering tools prevents the users from applying proper heuristics and strategies to optimum decisions (Iyengar & Lepper, 2000). Also, due to lack of filtering tools, users’ attention gets divided between cognitive and metacognitive activities thereby impacting the activity of selecting an appropriate fund.

Funds are racked based on their asset class i.e. equity, fixed income, hybrid and fixed maturity plans. Each group has a tagline like ‘Invest to grow your money’ and ‘Invest for income’, which is nothing but framing. Also, since these taglines represent the domain of gain, it is very likely that it can influence the decision of a novice user, as prescribed by the prospect theory. (Kahneman, & Tversky, 2013). Since this salient information is first to be encountered, it can even lead to anchoring bias (Croskerry, 2002).

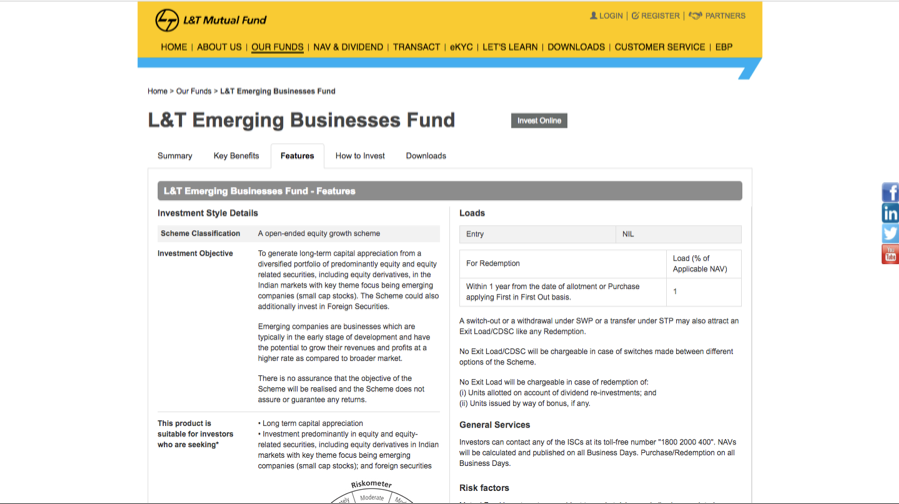

Figure 2: Fund details page

Selecting a fund navigates the user to the fund’s detail page, as shown in figure 2, where additional information about the respective fund is provided. The details include information very specific to the domain of mutual funds. Information is loaded with jargons and investment concepts making it difficult for novice users to comprehend. This difficulty to understand information can lead to confirmation bias as novice users will tend to gravitate more towards information that confirms their hypothesis formed by anchoring effect i.e. grow your money. As mentioned earlier, confirmation bias combined with anchoring bias can have a significant influence on decision making which can possibly lead to devastating outcomes (Croskerry, 2002).

As mentioned earlier, experts approach decision making in a quite different fashion than novice users. This holds true in L&T mutual funds case as well. As seen in figure 1, L&T mutual funds display fund names without any supporting information. In case of experienced or expert users, this lack of supporting information can lead to irrational decision making as experts are able to retrieve choices quite rapidly from their long-term memory, thereby choosing the same funds that earlier gained better returns (Wickens et al., 2012, p. 278). Providing supporting fund information can draw experts’ attention to key data points like decreasing or increasing fund performance, enabling them to make informed choices.

(Naqvi, Shiv, & Bechara, 2006) states that “The somatic-marker hypothesis is a neurobiological theory of how decisions are made in the face of uncertain outcome. This theory holds that such decisions are aided by emotions…”. ‘Somatic markers’ are feelings in the body corresponding to certain emotions. For example, the association of rapid heartbeat with anxiety or nausea with disgust. Such feelings can heavily influence decision making. Investing in a fund is a risky activity that can lead to uncertain outcomes. Therefore, it is imperative to prevent the involvement of emotions while investing in particular mutual funds. Displaying funds with supporting data can reduce the involvement of emotions and enable users to make informed selections.

4. Conclusion

The paper began with a brief description of metacognition and its parallel association with cognition. The paper further, described metacognition in decision making using various hypothesis and research related to framing, biases, and emotions. The paper then emphasized on the different decision-making styles and approaches in expert and novice users. Towards the end, the paper evaluated the L&T mutual fund’s website against metacognition in decision making and provided appropriate recommendations.

To build an enhanced user experience, it is imperative for UX designers to understand the parallel involvement of metacognition in cognition and to learn about various aspects of metacognition in decision making in order to let users to make rational, logical, optimal or informed choices.

References

Bechara, A. (2004). The role of emotion in decision-making: evidence from neurological patients with orbitofrontal damage. Brain and cognition, 55(1), 30-40.

Croskerry, P. (2002). Achieving quality in clinical decision making: cognitive strategies and detection of bias. Academic Emergency Medicine, 9(11), 1184-1204.

Dew, N., Read, S., Sarasvathy, S. D., & Wiltbank, R. (2009). Effectual versus predictive logics in entrepreneurial decision-making: Differences between experts and novices. Journal of business venturing, 24(4), 287-309.

Edwards, W. (1954). The theory of decision making. Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 380-417. American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/h0053870

Fishburn, P. C. (1970). Utility theory for decision making.

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive–developmental inquiry. American psychologist, 34(10), 906.

Halpern, D. F. (1998). Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains: Disposition, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring. American psychologist, 53(4), 449.

Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: can one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 995–1006. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.995

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (2013). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In HANDBOOK OF THE FUNDAMENTALS OF FINANCIAL DECISION MAKING: Part I(pp. 99-127).

Kühberger, A. (1995). The framing of decisions: A new look at old problems. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 62(2), 230-240.

Kuhn, D. (2000). Metacognitive development. Current directions in psychological science, 9(5), 178-181.

Lesgold, A. M. (1983). Acquiring expertise (No. UPITT/LRDC/ONR/PDS-5). PITTSBURGH UNIV PA LEARNING RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CENTER.

Meichenbaum, D. (1985). Teaching thinking: A cognitive-behavioral perspective. Thinking and learning skills, 2, 407-26.

Naqvi, N., Shiv, B., & Bechara, A. (2006). The role of emotion in decision making: A cognitive neuroscience perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(5), 260-264.

Schraw, G., & Moshman, D. (1995). Metacognitive theories. Educational psychology review, 7(4), 351-371.

Slagter, H. A., Lutz, A., Greischar, L. L., Francis, A. D., Nieuwenhuis, S., Davis, J. M., & Davidson, R. J. (2007). Mental training affects distribution of limited brain resources. PLoS biology, 5(6), e138.

Wickens C, Hollands J, Banbury S, & Parasuraman R. (2012). Engineering Psychology and Human Performance (4th ed.). Psychology Press.